Who Made Medicine What It Is

The path to modern healthcare is lined with the names of indispensable pioneers who changed the course of humanity. It's paved by individuals who asked better questions and refused outdated answers. Some stood alone, and others built on forgotten knowledge, but all left behind tools or systems still used today. Here, we share twenty names that shaped the world you live in—medically.

1. Hippocrates

This man broke traditions. In 5th-century BCE Greece, Hippocrates threw out superstition and placed logic at medicine's core. He blamed natural causes for your body's symptoms, not superstition, and penned the Corpus Hippocraticum, which shaped clinical observation. His oath still echoes in hospitals today.

2. Marie Curie

In the late 1800s, Curie uncovered polonium and radium. Her findings not only won Nobel Prizes but also revolutionized medical diagnostics and cancer treatment. During WWI, her mobile radiography units scanned over a million soldiers, guiding emergency surgeries on the battlefield.

Unknown authorUnknown author on Wikimedia

Unknown authorUnknown author on Wikimedia

3. Edward Jenner

Jenner exposed his gardener's son to a health risk in 1796, but he did it for science. He used cowpox to shield the boy from smallpox. It's revolutionary because you're alive to read this. By 1980, smallpox became the first disease humans eradicated through vaccination.

John Raphael Smith on Wikimedia

John Raphael Smith on Wikimedia

4. Florence Nightingale

Statistically brilliant, Nightingale didn't just bandage wounds but reinvented hospital care. In 1854, at Scutari, her charts exposed horrifying sanitation failures. She used data to prove that clean environments save lives and later founded the first nursing school to train professionals with a purpose.

Unknown authorUnknown author on Wikimedia

Unknown authorUnknown author on Wikimedia

5. Ignaz Semmelweis

Semmelweis noticed something horrifying in 1847: doctors spreading childbed fever between births. His solution was simple—handwashing. Ridiculed and institutionalized, he died before germ theory vindicated him. Today, neonatal wards across the globe owe their safety to his insistence on clean hands.

6. Jonas Salk

Kids lined up for sugar cubes in the 1950s, and Salk made sure those cubes ended polio's terror. Refusing to patent his vaccine, he said, "Could you patent the sun?" His research inspired the Sabin oral vaccine, which helped expand immunization worldwide.

SAS Scandinavian Airlines on Wikimedia

SAS Scandinavian Airlines on Wikimedia

7. Joseph Lister

Lister sprayed carbolic acid during surgery and transformed medicine. Before 1865, operating rooms were death traps, and he believed germs were the killers. Thanks to his antiseptic methods, post-op death rates were cut in half. Surgeons today still honor his legacy by sterilizing tools and wearing protective gear.

Walter William Ouless on Wikimedia

Walter William Ouless on Wikimedia

8. Elizabeth Blackwell

Persistence wore a white coat in 1849, as Blackwell became the first woman to earn a U.S. medical degree—after being admitted as a joke. She later co-founded the New York Infirmary for Indigent Women and Children, expanding care for underserved patients.

Joseph S. Kozlowski on Wikimedia

Joseph S. Kozlowski on Wikimedia

9. Henrietta Lacks

No consent or compensation, yet Henrietta's cells continued to multiply endlessly. In 1951, a cervical tumor taken during treatment led to the immortal HeLa line. You've benefited from her through polio vaccines and cancer research. Today, bioethics standards worldwide trace back to how her legacy was misused.

10. Virginia Apgar

Apgar made the strength of a baby's heartbeat measurable in 1952. She introduced a five-point newborn evaluation that is still used today. It helped reduce global infant mortality by flagging early distress. Hospitals worldwide use her scoring system within a minute of birth.

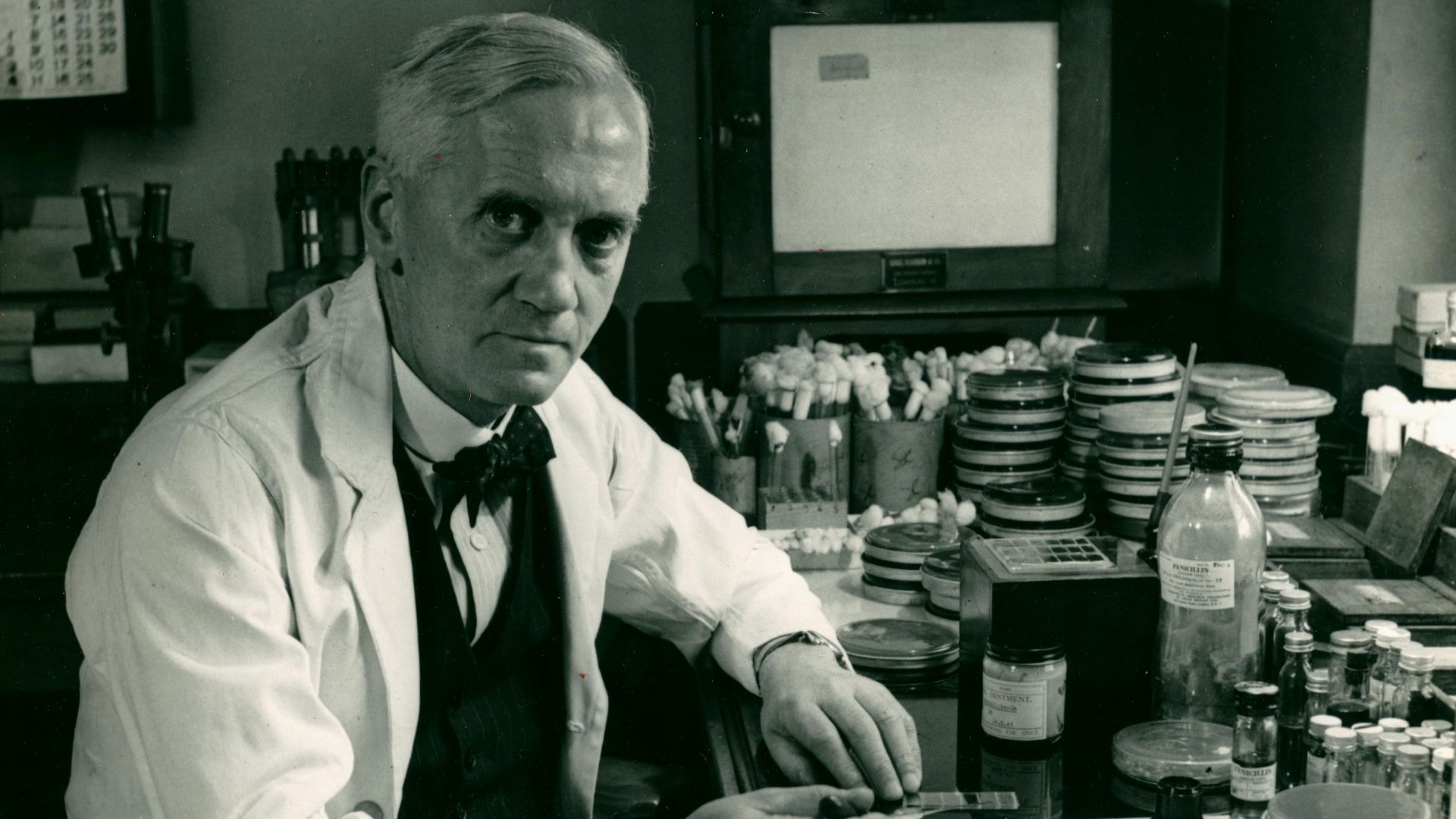

11. Alexander Fleming

Mold grew on an abandoned petri dish, and history shifted. Fleming noticed it was killing bacteria in 1928. That mold was Penicillium notatum. Penicillin soon became the world’s first widely used antibiotic. Within two decades, WWII battlefield infections dropped dramatically.

12. Clara Barton

During the Civil War, Barton ran toward chaos and wounded soldiers. She brought supplies and care to battlefield hospitals. Afterward, she founded the American Red Cross in 1881. Her model for organized disaster response now operates in over 180 countries worldwide.

Mathew Benjamin Brady on Wikimedia

Mathew Benjamin Brady on Wikimedia

13. Wilhelm Röntgen

Röntgen discovered X-rays in 1895 by accident while testing cathode rays. His wife's hand became the first medical X-ray image. Within weeks, physicians used the technology. Diagnostic medicine took a quantum leap, and your chest scan owes him credit.

14. Rosalind Franklin

Crystals and camera film led Franklin to the structure of life. In 1952, her Photo 51 captured DNA's double helix, which enabled Watson and Crick's breakthrough. While she wasn't credited in her lifetime, genetic medicine—from ancestry kits to cancer treatments—rests on the clarity she revealed.

CSHL, derivative work Lämpel on Wikimedia

CSHL, derivative work Lämpel on Wikimedia

15. Avicenna (Ibn Sina)

Ten centuries ago, Avicenna wrote The Canon of Medicine, a five-volume synthesis of Greco-Roman, Persian, and Islamic knowledge. It taught Europe's doctors for 600 years. Topics ranged from contagious diseases to pharmacology. Even basic pulse diagnostics today still echo lessons from his encyclopedic observations.

16. Andreas Vesalius

Forget Galen. In 1543, Vesalius dissected human corpses and disproved centuries of anatomical knowledge. His book De humani corporis fabrica mapped muscles and organs with astonishing precision. Today's medical illustrations and surgical training methods stem from his refusal to trust secondhand anatomy theory.

17. Paul Ehrlich

Ehrlich's "magic bullet" idea led to Salvarsan in 1909—the first effective drug for syphilis. He laid the groundwork for chemotherapy and coined the term “antibody." Your immune-boosting medications exist because he believed chemistry could fight disease with surgical precision.

Unknown authorUnknown author on Wikimedia

Unknown authorUnknown author on Wikimedia

18. Rebecca Lee Crumpler

After the Civil War, Crumpler treated newly freed Black patients in the South while battling racism at every turn. In 1864, she became the first Black woman to earn a medical degree in the U.S. Her book, A Book of Medical Discourses, preserved vital pediatric knowledge.

Unknown authorUnknown author on Wikimedia

Unknown authorUnknown author on Wikimedia

19. Rudolf Virchow

Virchow’s 1858 theory shifted pathology from mysticism to microscopes. Cells, not spirits, cause disease. He also tied poverty to illness, coining "social medicine." Public health reforms—like sanitation and housing codes—trace back to his idea that society's sickness must be diagnosed just like a fever.

Tucker Collection on Wikimedia

Tucker Collection on Wikimedia

20. Tu Youyou

After digging through ancient Chinese remedies to fight malaria, Tu extracted artemisinin—today's frontline antimalarial—in 1972. Despite having no Western training, millions survive because of her work. It wasn't until decades later that she got a Nobel Prize.

KEEP ON READING

10 Pre-Workout & 10 Post-Workout Tips To Follow